If there is anyone doubting the potency of Naira Marley’s name, that person better have a rethink. For a long time, there hasn’t been an artiste who has assumed so much notoriety, one whose antics are debated with so much nuance. People like to talk (and write) about Naira Marley, but what has the man himself got to say?

Till date, his most famous proclamation was the question of whether he engaged in internet fraud. The resultant song, “Am I A Yahoo Boy,” led him to dark waters, where he thrashed about, and it seemed he would be submerged in its murkiness. He didn’t, and he rose, with his hand simulating masturbation, voicing yet another proclamation, two words: Jo Soapy.

Since that song, Naira Marley would go on to become something of a maverick, a leader of the Marlians. A pseudo-woke group masquerading as dissents, the buzz would be caught, by everyone really. Those who didn’t like Naira Marley still danced (or found themselves doing so) whenever “Soapy” came on, perhaps only managing to censor themselves by not doing the infamous simulation. On Twitter, someone jokingly said that Naira Marley had entered legend status because stickers of his face were now being pasted on danfo buses and trailers.

That Naira Marley has navigated his way to this position is proof of his ingenuity. Merging the philosophical with the Street, he has found a reliable persona which feeds consumerism at the intensity it demands. With some style, too. The most pronounced of this is his declarations, delivered with the unmistakable arrogance of his Peckham accent. “Mafo” had the line “You want me to spend the money your daddy can’t spend on you” and “Bad Influence,” which was his first explicit attempt at sparking a conversation about his antics, featured the Lucky Dube–esque “We want school but they give us prison.”

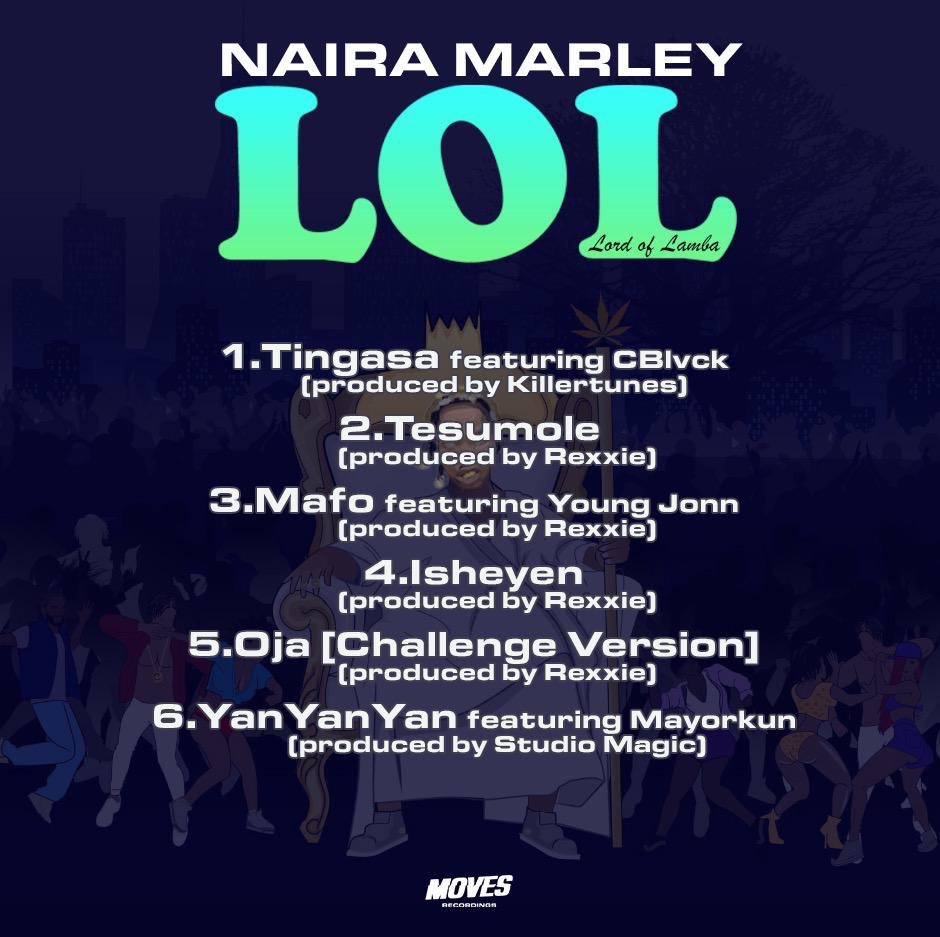

Lord of Lamba (LOL) EP Track list

In the streets, these declarations are collectively grouped under a singular term, “Lamba.” To one unaccustomed to the term, it incorporates all that is bold and persuasive, a sweet tongue kinda situation, lyrical deliveries learned by the street kid in order to navigate a day-to-day life which doesn’t promise safety. Naira Marley, having lived in the ghettoes of Agege and Peckham, I will assume, has long dabbled in Lamba, and has employed it to ensure survival.

Naira Marley is, alas, no longer Afeez Fashola, nor is he “the Issa Goal crooner” as he used to be addressed by. Nowadays, the dreadlocked act plays in the big leagues and has performed (or will) in some of the biggest platforms available to an artiste of his kind. He is, in his latest declaration, a Lord.

Lord of Lamba is rightful consolidation on a most massive year. With most of his celebrity friends (Wizkid, Davido, Burna Boy & Zlatan Ibile) releasing projects to mark the year and its many success, Naira Marley couldn’t be left out. And how fitting it will be an appraisal to his defining quality.

Some of his other qualities is his reliance on percussion-heavy beats, and an energetic vocal delivery which seems to draw strength from his bold statements. “Tingasa,” LOL’s opener, features all these; the Killertunes-produced song, with a little variation in its drum pattern, is a child of the Soapy prototype. Perhaps, the choice of a producer who isn’t Rexxie is an attempt at some variety (which fails).

In a project of six songs, Rexxie produces four. Accredited with fashioning the sound Naira Marley has tapped so well, he turns to the trusted once more. “Mafo” is perhaps, the most realized song in the sound scope. A huge song of its own, it makes a return in LOL, sandwiched between “Tesumole” and “Isheyen,” the latter which seems to sample Kizz Daniel’s “Mama.” The song which follows, “Oja,” still threads the sound charted, with almost no variation, five songs in, to the breakneck pace of these party-ready bangers, which were most likely curated with eyes on ruling the December festivities.

“Yanyanyan,” with its tinkling keys and bouncing drums, sees Naira Marley and Mayorkun play provocateur, with the Marlian leader alluding to being in your face like… (insert song title). It’s a good closer, one which seemed saved up for a while now. On the day he wears a different-than-usual skin, Naira Marley opens his hands and declare his greatness. He was in similarly bullish mood when he shared the project with his fans on Twitter.

Where’s all the haters that said Naira Marley will die down before December ? Do u wanna pick another month or u’re still sticking to December? https://t.co/iKDmaYcIB4#LOL ep out now

— nairamarley (@officialnairam1) December 18, 2019

Therein, LOL presents itself as the work of an artiste who’s convinced of his place. Naira Marley isn’t afraid of being predictable: he knows he is powered by a force more urgent than the demand for robust music. He knows, and that’s why he fancies himself a Lord. Five songs out of this six track EP is nothing new –nothing but recycled material. But it is material which sells (and primarily because it is Naira Marley’s material), there’s a good chance people will yarn dismissive woke stuff on social media, then go play and dance to these songs. I can almost imagine Naira Marley laughing out loud.

The post Naira Marley’s “LOL” Is Nothing New, But You’ll Bump It Anyway appeared first on Latest Naija Nigerian Music, Songs & Video - Notjustok.

from Latest Naija Nigerian Music, Songs & Video – Notjustok

via EDUPEDIA

Comments

Post a Comment